Caribbean governments have rightly focused on the severe consequences for their countries of the withdrawal of correspondent banking relations from regional banks by international banks, particularly those located in the US. But there will also be serious consequences for other parts of the world, particularly the US, if the current troubling trend remains unchecked.

The gravest immediate threat is to Caribbean countries certainly. This not an abstract issue, restricted to the banking sector or governments. The adverse effects will spare no one. They will affect every sector of economic and financial activity, including tourism, importers and exporters of goods, and individuals who either send money abroad or receive it.

In the tourism sector, airlines will not be able to transfer monies earned in the Caribbean to their home locations, cruise ships will not be able to pay for their passengers who sail to the region, hotels will not be able to purchase the food and beverages they import for the tourism industry, even motor car dealers won’t be able to pay for vehicles they bring in to the country. What’s more, individuals abroad who send money to their dependent relatives will find it impossible to do so. And so the list goes on.

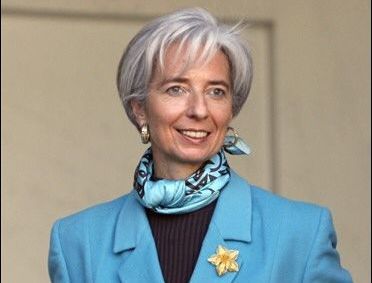

Without correspondent banking relations, all financial transactions with the US — and many other countries — will come to a halt. These relations are so important globally that it caused the managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Christine Lagarde, to observe in July during a major policy address that: “Correspondent banking is like the blood that delivers nutrients to different parts of the body. It is core to the business of over 3,700 banking groups in 200 countries.”

A recent World Bank study of the impact of de-risking on correspondent banking globally found that 75 per cent of large international banks have reduced their total number of correspondent banking relationships, and 80 per cent reported that they had severed all relationships in some jurisdictions. The study also revealed that about 55 per cent of banks receiving correspondent banking services reported a decline in the availability of those services, with about 70 per cent of those reporting a decline indicating that the decline was “significant”.

But, the Caribbean is the region in the word that is hardest hit. Undoubtedly, this is because of two decades of the European Union Commission, members of the US legislature, the US Government, and even State governments in the US branding Caribbean countries as tax havens — even though the evidence does not support the contention.

According to the IMF, at least 16 banks in five Caribbean countries had lost all or some of their correspondent banking relationships as of May 2016. The same study reports that, in Belize, only two out of nine banks (representing 27 per cent of banking system assets) have been successful in maintaining correspondent banking relations with full banking services. And in The Bahamas, five financial institutions (accounting for 19 per cent of banking system assets) have lost at least one correspondent banking relationship. But, no Caribbean country has been spared, and banks in all of them, including in the Eastern Caribbean, Barbados, Jamaica and Guyana, are currently facing the real prospect of losing all correspondent relations with US banks.

There are ways of getting around the problem, but they are expensive and their permanence is not assured. For instance, these transactions can continue through willing banks in intermediary countries that enjoy correspondent banking relations with global banks in the US. But the cost of such transactions will be high, and in many cases unaffordable. In any event, they would push up costs, making the Caribbean uncompetitive. Further, the facility could be cut off if global banks in the US apply onerous conditions.

That is why the Global Stakeholders’ Conference on ‘Correspondent Bank Relations; De-risking; and Branding Caribbean Countries as Tax Havens’, being held in Antigua on October 27 and 28, is vitally important.

Hosted by the Antigua and Barbuda Prime Minister Gaston Browne, who has responsibility for financial affairs in the quasi-Cabinet of Caribbean Community (Caricom) heads of government, the conference will gather representatives from international financial institutions, regulatory bodies, governments, and banks in a ‘closed-door’ meeting to try to find solutions from frank discussions. Christine Lagarde is sending her deputy managing director, Zhang Tao, to represent her. Zhang, appointed two months ago, is the former deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China.

The global stakeholders attending the conference will be keenly aware that what Caribbean countries are facing is grave limitation of a country’s ability to undertake international trade or financial transactions. That would mean collapse of businesses, rapid escalation of unemployment, increase in poverty, and a huge reduction in any government’s capacity to provide its people with adequate health care, education and protection.

The dreadful effects of such a woeful transformation of the Caribbean would not be limited to the Caribbean Sea. Inevitably, economic refugees will end up on the shores of US territory and other wealthy countries and there would be an increase in the drugs trafficked through the region as the unemployed and the desperate seek means to survive. Additionally, money would find unregulated and unstructured ways to cross borders, defying the very money laundering activities that withdrawing correspondent banking relations are trying to suppress.

Further, if Caribbean countries cannot pay or be paid for the goods and services they trade with the US, they will be forced to turn their attention elsewhere. In such a case, the US will lose revenues and jobs. The total loss may be minuscule, given the relative small size of Caribbean markets; nonetheless, they will have an impact.

Of greater importance is the loss of US influence in a region that sits next door. That vacuum will be filled by some other countries or group of countries that the US might not appreciate. But, the people of the Caribbean have to survive. It will not be that they love the US any less, but they love life more.

By failing to respond swiftly, creatively and positively to the destructive effects of the withdrawal of correspondent banking relations, US decision-makers in government, in regulatory bodies, and in the legislature might be making a stick to beat their own backs.

Sir Ronald Sanders is Antigua and Barbuda’s ambassador to the US and Organisation of American States; an international affairs consultant; as well as senior fellow at Massey College, University of Toronto, and the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, London. He previously served as ambassador to the European Union and the World Trade Organization and as high commissioner to the UK. The views expressed are his own. For responses and to view previous commentaries:

www.sirronaldsanders.com

source: http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/columns/Banking–Is-the-US-making-a-stick…